A Story About My Dad, Warrior, Photographer

With Sandy Brown Jensen

Once upon a time in the early, anguished years of the last century, two great world wars devastated the world. Those who fought and survived, The Great Generation they were called, came home with psychological wounds that scarred that entire generation like an ancient high water mark will slash the cliff above the quiet sea.

(CAPTION) On the Oregon Coast, ancient beaches and shell middens leave long slashes in the cliffs that are buried and forgotten memories until the sea reveals their secrets once again.

(PHOTO CREDIT) Sandy Brown Jensen

My father was one of those survivors. He came home to the Pacific Northwest, married his sweetheart and had four children; I’m #2.

(CAPTION) After the war was over, Warren and Mickey built their home along the Wenatchee River on the eastern slope of the Washington State Cascade range in a bend in the Wenatchee River.

(PHOTO CREDIT) Jan Cook Mack, oil painting, “This is Where We Live: Wenatchee River, August.” http://jancookmack.com/oil-paintings.html

When my father was discharged from the U. S. Army, his service rifle came home with him, where it hung over our stone fireplace with his hunting guns. We lived a somewhat subsistence lifestyle in those early days, so I grew up with the top two guns in the rack regularly coming and going depending on whether it was deer, elk, or bird hunting season. Whatever high water tide mark of the war there was in him, he kept under a cone of silence.

(CAPTION) My dad Warren Brown with a bear and an antelope and his bolt action hunting rifle.

(PHOTO CREDIT) Brown Family archives.

During those early years of the 1950s, my dad took up photography. He had a Leica he loved so much that he named his purebred German Weimaraner hunting dog after it.

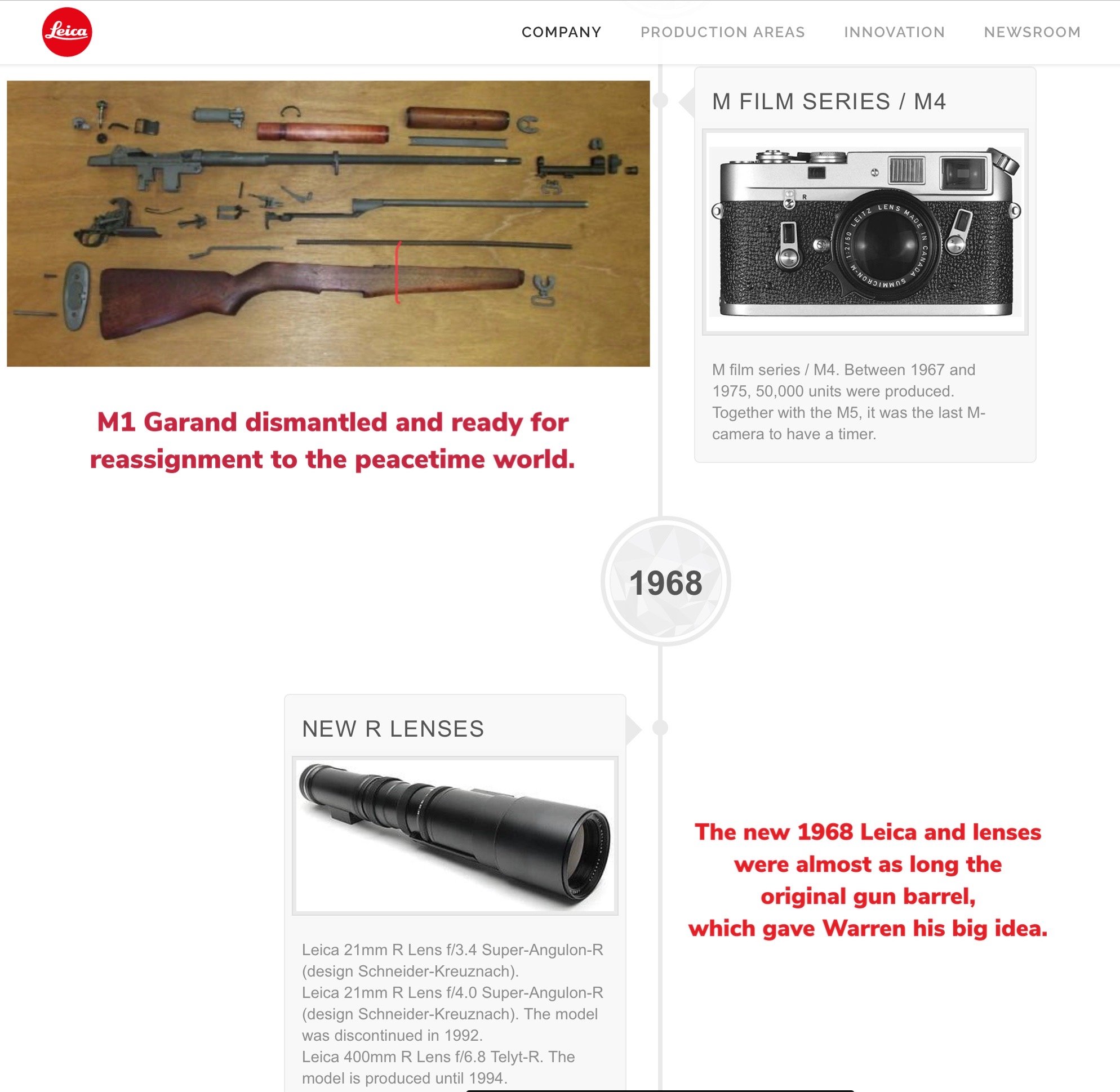

One day, I noticed his Army gun had disappeared. He had a wood-shop as well as an ammunition reloading station in the basement alongside my mother’s custom drapery studio. When I was sent downstairs to get a jar of peaches from the home canning shelves, I saw the gun dismantled on his steel reloading desk. It looked odd, dismembered like that, the heavy, dark, lethal barrel set aside from the grimy wood of the gunstock.

Nobody really knew what he was doing with the gun, but one day we were all at the dinner table when he announced he had something to show us: he had mounted his new Leica with its long lens on the gunstock. That lethal trigger had been replaced with a release cable. He had refinished the wood, and the rich walnut gleamed in the evening light.

(CAPTION) Illustration of a M1 Garand dismantled as my father did in his basement workshop, with a Leica historical website image of my father’s 1968 Leica and lens upgrade. His original was built in the late 1950’s.

During the Vietnam era, there was a famous photograph of a young man placing a flower in the barrel of a rifle. That image became iconic because of the symbolism of turning the guns of war into the flowers of peace.

(CAPTION) The Flower Power photograph taken during the March on the Pentagon, October 21, 1967

(PHOTO CREDIT) Bernie Boston

In his own way, that’s what my dad had done. Whatever terrible memories of D-Day were connected to the rifle, his constant companion as he crossed what became known as “Bloody Omaha '' Beach, he transmuted into the peace of his post-war passion: photography.

I grew up seeing my father’s view of the world—the delicate macros, the landscapes that drew him as he and my Mom traveled to the Southwest and Mexico. In his photos, I see his love of family, his early experiments with portraiture, his efforts to catch on film anything with wings. He wasn’t above chasing a butterfly across a meadow or dodging waves on a beach trying for shorebirds.

(CAPTION) My mother Mickey Brown was the most frequent sitter for Warren’s early efforts at portraiture.

(PHOTO CREDIT) Warren Brown Archives

My father taught me to change ashes into beauty; when mourning to use art as the oil of joy; and to wear the garment of praise when weighted down by the spirit of heaviness (to paraphrase Isaiah 61).

(CAPTION) Warren delighted in chasing butterflies across the meadows. Keep in mind, he was shooting color film, and every excited frame cost him money.

(PHOTO CREDIT) Warren Brown Archives

Today, when I’m out photographing, I feel my father’s spirit with me, interested in new technology, looking out at the world with my eyes, and very clearly, when I’m hesitating over a composition, I hear him shout with excitement, “Shoot! Shoot! Shoot!”

And I take the shot for him. Together we still work to change the terrible past into the peaceful images of the present.

(CAPTION) Thanks to the unimaginable efforts of the members of The Great Generation like my dad, I am able to go out every day and confidently photograph The Peaceable Kingdom.

(PHOTO CREDIT) Sandy Brown Jensen

Sandy Brown Jensen

Oregon photographer Sandy Brown Jensen is the co-host for Viz City, KLCC’s Arts Review Program. Sandy’s MFA is in Poetry, and she has retired from a career in teaching writing at Lane CC. Her interest in imagistic poetry hasn’t changed, but she has moved from the pen to the camera. Her primary interests are in alternative photographic processes, including gold on vellum prints, as well as photo essays.

Sandy lives in Eugene, Oregon. She is happily married to her Shakespeare scholar husband, Peter, and they are ruled by two cats in a house not too far from the Willamette River. She is an avid hiker and backpacker as well as a passionate home cook. Her favorite city is Paris.

I Dream in Gold Photography

Sandy Brown Jensen

340 N. Grand

Eugene, OR 97402

541 321 3210